Parashat Va’era

Parashat Va’era is the fourteenth weekly portion in the Torah and the second in the Book of Exodus (6:2-9:35).

In the first section (6:2-30), Moses confronts the reality that he will be unable to lead the Israelites out of Egypt by normal means. Neither the Egyptian masters nor the Hebrew slaves believe that anyone cares about their fate. In fact, the Torah chooses this moment to give us the genealogy of Moses of Aaron, filling in the gaps in the family tree, naming their forebears, parents and cousins. In Aaron’s case, we meet his in-laws, children and grandchild. (All will have important roles later.) The message is clear: these are human beings charged with a divine mission.

As the next section (7:1-8:19) begins, we see why it is important to make this point: “The Lord said to Moses, ‘See, I have made you like God to Pharaoh, and your brother Aaron will be your prophet.’” Since Moses and Aaron are about to perform godlike wonders, it is imperative that we recognize they are human vessels for God’s will.

The signs commence with Aaron’s staff turning into a serpent in Pharaoh’s throne room. However, since Pharaoh’s sorcerers (chartumim, replacing the scholarly kohanim of Joseph’s time) can mimic this, he remains unimpressed. Thus, the Ten Plagues commence, with the first three striking the very water and earth of Egypt. The Nile is turned to blood, then frogs emerge from it; the dirt itself teems with lice. While the chartumim reproduce the signs upon the Nile, the third is beyond their abilities, and they admit: “It is the finger of God!” However, Pharaoh refuses each time to let the people go.

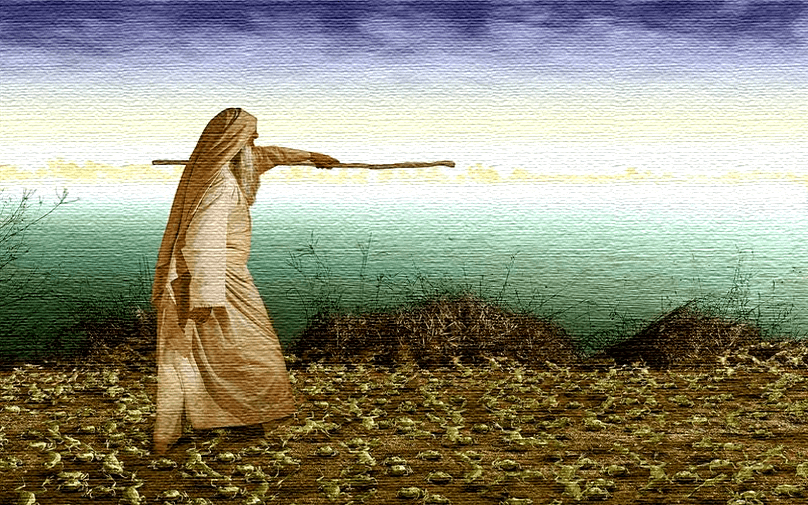

In the final section (8:20-9:35), four more plagues strike Egypt. However, there is a new element introduced: the distinction that God makes between His people and the areas in which they live, on the one hand, and Pharaoh’s people and land, on the other. Still, though God spares the Hebrews and smites the Egyptians, Pharaoh is unmoved. Wild animals, pestilence and boils lay Egypt low, but as soon as there is relief, Pharaoh hardens his heart. Moses even reaches out to the common Egyptians before the seventh plague, fiery hail: anyone who fears God need only go inside to be spared! Pharaoh seems to crack in the face of this destruction, recognizing God’s righteousness and his own sinfulness. However, once again, when the pyromaniacal precipitation passes, he (and his servants) reiterate their refusal to release the Hebrews.

The portion from the Prophets comes from Ezekiel 29, in which the prophet is told: “Thus says the Lord God, ‘Behold, I am against you, Pharaoh king of Egypt, the great serpent that lies in the midst of his rivers, who has said, “My Nile is mine, and I myself have made it.”’” This echoes Moses’ mission to a different Pharaoh a millennium earlier; indeed, turning Aaron’s staff into a serpent is the first sign, presaging the Ten Plagues.