Parashat Shemot

Parashat Shemot is the thirteenth weekly portion in the Torah and the first in the Book of Exodus (1:1-6:1).

In the first section (1:1-2:10), the Torah tells us that once Joseph’s brothers and their generation passes, a new king arises over Egypt who does not know him. He frightens his people by telling them that the Israelites are a threat; they are too numerous, too powerful and too crafty. Egypt will be overrun by them, and they will eventually take up arms against their host country. Initially, they are merely taxed, but the hatred of the Hebrews (a term not used since before Jacob came down to Egypt) transforms into enslavement, infanticide and genocide.

Nevertheless, the worst of this cruelty is met with resistance, particularly on the part of women. Pharaoh’s initial plan to the males Hebrews killed at birth is thwarted by the midwives Shiphrah and Puah. Some traditions say these midwives were Hebrews, others that they were Egyptians; in either case, they use Pharaoh’s racist view of the Hebrews against him.

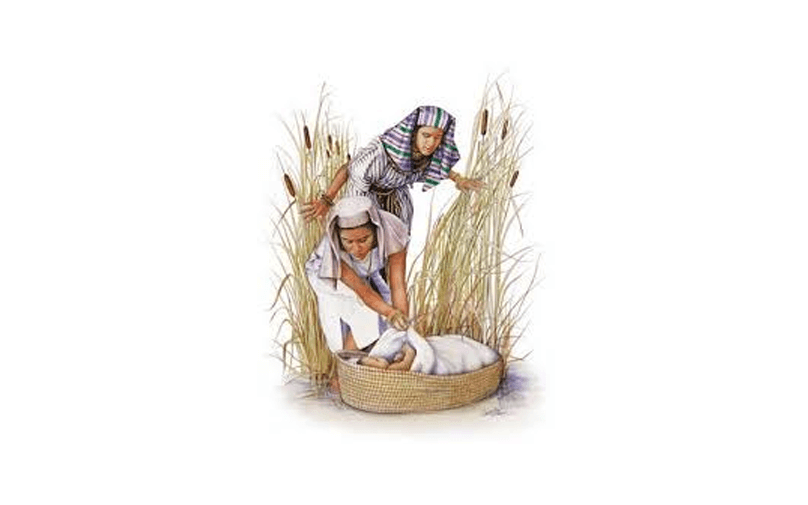

Pharaoh issues a new decree: throwing all the boys into the Nile. Nevertheless, a Levite woman hides her newborn, putting him in an “ark” (teiva, just like Noah’s) in the river when she can no longer do so. The baby is discovered by Pharaoh’s daughter, who pities him. The boy’s sister offers to find a Hebrew wet-nurse, which Pharaoh’s daughter agrees to. While we are not privy to what the princess says to her father, the harsh decree seems to be set aside, as by the time the boy is weaned, Pharaoh’s daughter is able to adopt him. She names him Moses.

In the next section (2:11-4:26), we encounter the adult Moses. He is moved to action when he sees injustice and violence, but ends up having to flee Egypt. In Midian, he marries and settles into life as a shepherd, but God appears to him in the Burning Bush to send him to redeem Israel. Moses finds it difficult to accept his mission, angering God. Once again, a woman comes to the rescue: Moses’ wife Zipporah circumcises their son, symbolizing that their family is part of Israel and Moses cannot escape his destiny.

Indeed, in the final section (4:27-6:1), Moses finally finds his voice. With his brother Aaron at his side, he confronts Pharaoh for the first time; and when the demand “Let my people go!” is met with a command from Pharaoh to make the slaves’ labor harder, Moses has the audacity to confront God and demand: “Why have you sent me?” Thus, a leader is born.

The portion from the Prophets differs among various Jewish communities: Ashkenazic Jews read of the ultimate redemption in Isaiah 26, in which Israel’s exiles will be returned from Assyria and Egypt to Jerusalem; Sephardic Jews read Jeremiah 1, which describes the selection of the prophet, much like Moses; and Yemenite Jews read Ezekiel 16, which describes how Israel first became a nation amidst Egyptian slavery.